a pregnant monk: a gendered study of body horror

a medievalist, queer, feminist, theoretical approach to the genre of horror

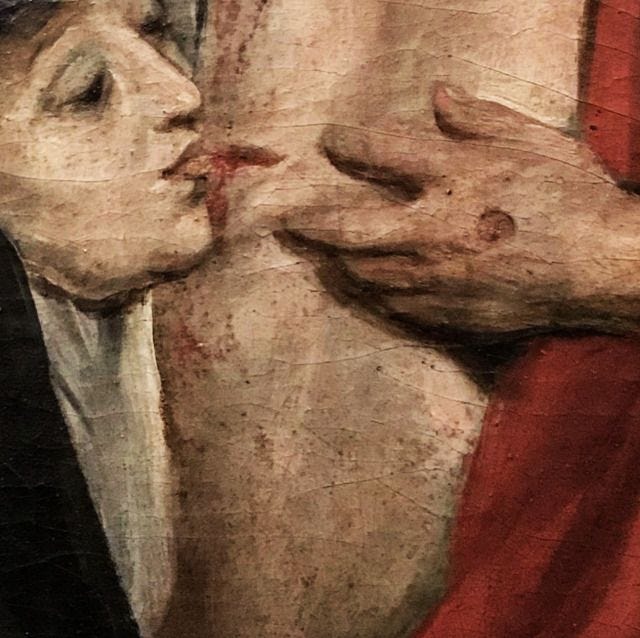

Catherine of Sienna drinks blood from the side wound of Christ, 1600.

Firstly— Most of the writing I’ve done this month has been for finals. I’m really proud of this work, for my WGSS “embodied gender” class, so I thought I’d share it here. Bear in mind certain academic language + references were required for the assignment, as I’ve not made any changes to the submitted paper. Otherwise, enjoy!

Secondly— this essay owes much to Viktor Athelstan for the story Brother Maternitas, published in queer horror anthology, Your Body is Not Your Body.Read here!

The gendered nature of shame, and the subsequent effect of shame upon the body is central to the genre of body horror, which explores embodied experiences through morbid imagery and horror tropes. In this paper, I will be exploring how body horror reflects the inscription of shame upon the gendered body. This analysis will touch on several themes from this course including masculine/feminine dualism, pregnancy, trans bodies, and abjection. The aim of body horror, as a genre, is to create or emphasize the abject body. If abjection is the process by which a body is made disgusting by its non-normativity, then that body is effectively inscribed with shame. It is important to note that shame functions socially in order to undermine one’s position in society. Patriarchally normative society encodes the female body and its functions with shame and thus marks it as an inferior body. Shame effectively conditions the female body into passivity and submission under the patriarchal order.

Bearing this in mind, Xavier Aldana Reyes provides foundational theory for body horror in Abjection and Body Horror, drawing upon Julia Kristeva’s theory of the abject as the cultural signification of which bodies are inscribed as disgusting. Abjection is, in essence, “‘the process by which something or someone belonging to the domain of the degrading, miserable, or extremely submissive is cast off,” (Kristeva in Reyes, 395). Because the female body expels “polluting objects,” (396), that is, menstrual blood, it becomes inherently defined as an object of disgust. To be disgusting is to harbor shame. Furthermore, “the female monstrous body in horror is intrinsically connected to patriarchal constructions of pregnancy, birthing, and menstruation as dirty, but also to the fear of castration” (Reyes 396). These concepts are exemplified to an extreme in the source that I will be subjecting my analysis to—a short story, titled “Brother Maternitas,” by Viktor Athelstan, published in Your Body is Not Your Body1.

“Brother Maternitas” is a short story set in a medieval monastery in the aftermath of a Viking raid. The story itself examines the construction of shame toward the feminized body within the medieval world and organized religion. Athelstan takes Reyes’ ideas about feminine abjection and furthers this theme by extending it to queer and trans bodies. To summarize the story, Brother Maternitas finds himself pregnant. It is later revealed that his body was magically transformed and impregnated by an embodiment of the devil in the form of a Northman. Brother Maternitas overhears a discussion between pregnant pilgrims and Brother Columba, who expresses envy for the womens’ pregnancies:

“‘The Virgin Mary blessed your wombs,’ Smiling, he pressed his fingers into his chest. ‘If I were not a man...’

‘You are a man,’ I said.

‘I know, Brother. You forget. Man, woman, in between, we are all God’s children and He sent His only son to labor on the cross as a mother labors in childbed. He spiritually nurses us pitiful humans with divine milk from His fertile bosom. Christ’s glorious side wound birthed the Church we all worship!’”

Brother Maternitas finds himself repulsed by Columba’s envy for what was deemed a filthy, inferior existence; doubly so because in a twist of dramatic irony, he himself is embodying this existence. In an act of desperation, he attempts to invoke a miscarriage. This leads him to fall into poor health, and the brothers care for him in the infirmary, where they find out that his body has been magically transmuted into a female one. He delivers a stillborn daughter, and in the night, the demon returns to inflict onto Brother Columba what was inflicted upon Brother Maternitas. Whereas Brother Maternitas was deeply scarred by his transformation as it was born from a violation, Brother Columba welcomes his change, grinning “in religious ecstasy.”

The first theme to be explored is the central dualistic conflict within the story: masculinity against femininity. While foundational queer and feminist theory debunks this binary thinking, the medieval mind was programmed to dualistic thinking: the world was seen through a lens of binaries, established by theorists like Aristotle, who posited that the female is everything the male is not. The perversive nature this dichotomy had on medieval social thinking is reflective in that Brother Maternitas felt he occupied an intrinsically feminized body within society due to the submissive nature of monastic life:

“I didn’t care how much Brother Columba argued that religious masculinity is masculine. Secular men mocked monks for a reason. I never should have allowed my lust to impede my reason... I submitted like a woman and now I’ve become one.”

Brother Maternitas draws a connection between his submission to the monastic lifestyle and femininity. As a product of a patriarchal society, his personal beliefs regarding womanhood reflect a greater social consciousness, which Janet Lee writes about: “women’s bodies connote words like earthy, fleshy, and smelly, reminding humans of their mortality and vulnerability.” If the female body connotes these deathly ideas, then it is made abject. The female body is made wild, of the earth, uncontrollable, and animalistic—a cultural contaminant—as opposed to the masculine ideal, which posits that control over the body and the natural world garners an inherent role of superiority. Thus, the situation of this story in a masculinized medieval environment serves to reflect the “deep-seated cultural perceptions of the female body as corrupting, contaminating, unclean, and sinful.” It is clear how the female body is encoded as an object of disgust: several aspects of the female existence such as pregnancy, the breasted experience, and menstruation will be scrutinized in this analysis in the context of this short story. These bodily occurrences are natural yet treated as vile. Bodies are often socially understood as indicators of the self, especially in a masculine context. For a body to do things like bleed, leak, and undergo great pain such as childbirth seemed, for a greater part of history, an indication of the inherent “natural” inferiority of those bodies. Lee posits that “woman is associated with life, while the other, her bleeding and oozing body is met with disgust, reminiscent of earthly vulnerabilities.” This thinking is clear in Brother Maternitas’ hatred of his self-due to his disgust towards his own body:

“A man controls the entirety of his body. He controls his mind, his emotions, his bodily fluids. Women leak. I leak.”

Patriarchally hegemonic society demands control over the body—autonomy is a masculine privilege. Men don’t leak, after all. They don’t ooze or bleed, as Lee points out. They are contained; women, supposedly being the opposite, are positioned as social contaminants. Rosaland Gill notes that the masculine body is constructed socially in such a way that it aims to be the ideal of the “morally accountable body.” This idea is achieved through the connotations of masculinity with bodily “management,” and control. Masculinity is bifurcated (Gill) in such a way that the body is conceptualized as an indicator of the value of the self. The self can—must — tame the body. A cultural precedent was set in stone ages before this story takes place by the very first woman’s inability to control herself. If Eve orchestrated the fall of man and women were cursed to bleed and bear children as punishment, it is clear how these bodily functions would have invoked a deep sense of shame. The biggest indicator of the feminine lack of control is menstruation, especially menarche—a quintessential marker of loss of agency both literally and socially. Menstruation is largely uncontrollable, so menarche marks both a literal loss of control over the body, but it also marks the body as socially feminine, objectified by its function and forced into a subservient social position. The cultural treatment of menstruation as something to be concealed, not discussed, and endured furthers the understanding of the feminine body as a shameful one. A natural occurrence with its keystone feature being its uncontrollability, menstruation is treated as a marker of difference, and, aligning with patriarchal thought, all that is different and other is intrinsically lesser-than.

What Brother Maternitas undergoes mirrors menarche. All at once his bodily autonomy is stripped from him. This is clear in the language with which he describes his changing, foreign, uncontrollable body: “when I wash in the privacy of my cell, the undeniability of my missing member swims in my head as I learn how to clean the new opening between my legs.” Brother Maternitas understands his newfound femininity as an absence of masculinity, reflecting the limitations of binary-gendered thinking. Iris Marion Young theorizes that the parallel to the phallus is not the vulva, but the breast. While the phallus offers empowerment to its bearer, the breasts are markers of inferiority. “The dichotomy of motherhood and sexuality...maps onto a dichotomy of good/bad, pure/impure,” (Young). Young’s observations reveal the social function of castration anxiety. Brother Maternitas understands his transformed body as a loss, rather than a change. The breasts are not treated as an alternative, but a lesser substitute for once was. Once again, that pervasive dualistic thinking transforms the embodied experience: both female sexuality and motherhood are treated as forms of submission. Iris Marion Young writes that “pregnant consciousness is animated by a double intentionality...subjectivity splits between awareness of [the self] and awareness of [one’s] aims and projects.” Brother Maternitas’ understanding of his self is corrupted. His pregnant consciousness is tinged with shame; primarily due to the nature of his body’s feminization, which he perceives as being made inferior by its uncontrollability. His aims—to be a virtuous Christian man, are this disrupted by the contamination of his body. The role of religion in this story reflects the role of shame as a tool of self-surveillance. The source of Maternitas’ shame is his body’s unmanageability, an indicator of feminine sinfulness. His shame is only that: his. While the social construction of gendered bodies through a moralistic lens provides a foundational reasoning for his shame, the way he experiences shame is ultimately unproductive and serves as a means by which he projects patriarchal thinking onto his body in an act of self-surveillance, essentially encoding his own inferiority. Shame is a means by which the mind does the work of the patriarchy.

His understanding of the feminine body as uncontrollable is one reminiscent of ideas present in Ahmed’s Fragile Bodies, which posits that queer and disabled bodies are similar for their situation within society as non-normative. Similarly, Young posits that the pregnant experience is treated as a disorder; the normative (male) body is understood as static, largely unchanging. If the male body is the ideal, then the female body is once again made inferior by its constantly changing nature. Pregnancy, a transcendental experience, is the ultimate embodiment of the feminine difference from the masculine. Just as the disabled body is made disabled by social expectations of bodily ability; the female body is made inferior by a medley of socially constructed misconceptions of female health and cultural opinions of female subservience. Taking this concept a step further, Brother Maternitas’ body is feminized in a queered way by its occupation in a masculine environment. As the story’s resolution suggests, this is a tale of body dysmorphia.

The extreme sense of self-hatred Brother Maternitas harbors speaks to a male understanding of the masculine self, as well as a greater cultural one of the feminine. Brother Maternitas is disgusted with Columba’s desire for femininity. They both experience gender dysmorphia in ways that reflect social constructions of gender. Brother Maternitas loathes all that is feminine as he believes it to be inferior. His body is thus dysmorphic to him as he no longer inhabits a body that aligns with his understanding of his role in society. Brother Columba, on the other hand, expresses discontent with his masculinity. The dual arc that takes place between the two is a projection of contemporary social beliefs onto an aspect of the past. Athelstan explores queered gender identity through a lens of shame and ignorance: Brother Maternitas cannot fathom why Columba could possibly want to be a woman if women are inherently inferior. He understands Brother Columba’s mystic reverence to Christ’s side wound as vile and sinful. This tidbit draws from medieval cultic beliefs surrounding the side wound of Christ, acquired during his torture on the cross. The medieval reverence for this imagery may reflect proto-queer understandings of gender amongst an otherwise normative culture. Brother Columba’s understanding of gender harkens back to Lee’s observations. The female body is dually associated with life and productivity in its birthing function: “He spiritually nurses us pitiful humans with divine milk from His fertile bosom. Christ’s glorious side wound birthed the Church.” Because Christ’s body is not wholly feminized, it is permissible for it to exhibit feminine attributes. There is a transience present in Columba’s thinking. He conceptualizes gender along the lived experience model, rather than Maternitas’ adherence to dualistic thinking which posits his body, as a feminized one, to a shameful one: “neither Christ nor Brother Columba will birth an abomination.”

Brother Maternitas is a story of morbidity. Rich in gory details—blood and bodily fluids leaking and polluting bodies, demons and torture, wounds and penetration—the body horror aspect of Brother Maternitas helps to enhance that pervasive sense of shame that stems from the body being made into an object of disgust. There is significant cultural precedence that spans millennia constructing the female body, or the male body’s feminine characteristics, as inherently disgusting. One of the most significant markers of differences between the embodied male and female experience is the ability to manage the body, and what better way to represent this lack of bodily autonomy that through a man transformed against his will to carry an abomination? If the horror genre reflects concerns within the social consciousness, then the infliction of horror upon the body serves to other those bodies. Body horror inscribes the othered body as abject, a reminder of death and otherness. Brother Maternitas’ body is subject to horror through the transformation of his body, which he understands as his whole self. The language of body horror present within the story reflects the cultural abjection of the female body, revealing the role that binary understandings of gender play in weaponizing shame as a means of further othering embodied experiences of femininity.

REFERENCES:

Sara Ahmed, “Fragile Bodies,” “Losing Confidence,” and “Queer Fragility” – selections from her blog Feminist Killjoys

Ahmed, Sara. “The Performativity of Disgust.” In The Cultural Politics of Emotion, NED-New edition, 2., 82–100. Edinburgh University Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1g09x4q.9.

Viktor Athelstan, “Brother Maternitas,” in Your Body is Not Your Body, Tenebrous Press, 2022.

Rosalind Gill, Karen Henwood, and Carl McLean, “Body Projects and the Regulation of

Normative Masculinity,” Body and Society 11, no. 1 (2005): 37–62

Sandra Lee Bartky, “Shame and Gender,” in Femininity and Domination: Studies in the Phenomenology of Oppression (NY: Routledge, 1990), 83–98

Janet Lee, “Menarche and the (Hetero)sexualization of the Female Body,” Gender and Society 8, no. 3 (1994): 343–62

Xavier Aldana Reyes, “Abjection and Body Horror,” on The Palgrave Handbook of Contemprary Gothic. Ed. Clive Bloom, 2020, 393-410.

Iris Marion Young, “Pregnant Embodiment: Subjectivity and Alienation,” in On Female Body Experience, 46–61

woah this genuinely blew me away. i don't see body horror being spoken about as a genre very often, so reading this unlocked an entirely new perspective for me. i will definitely be giving brother maternitas a read after this piece 🤍

not to sound dramatic, but I could read nothing but your works all day long